When we think of homelessness, we often imagine faraway places—shelters in America, tent cities in Europe, subway stations in bustling metropolises. But the truth is quieter in Singapore. It hides in plain sight.

It looks like someone sleeping under the staircase of an HDB block.

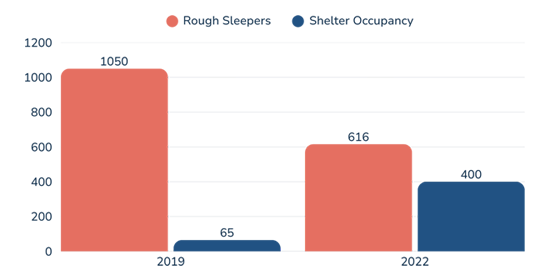

In the first nationwide street count conducted in 2019 by researchers from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), between 921 and 1,050 people were found sleeping rough in public spaces across Singapore.

In 2021, the number of rough sleepers decreased to 616, while shelter use increased significantly—from 65 to over 400. In total, 1,036 individuals were identified as homeless.A Pandemic Response: From Streets to Shelter

At first glance, it may seem like homelessness was significantly reduced. But the real story is more complex—and encouraging in some ways. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant national push to provide shelter for people with no permanent home

Community groups, government agencies, and social service organisations worked together to:

As a result, many who were previously sleeping in public spaces accepted support and moved into shelters. Shelter occupancy rose dramatically—from 65 beds in 2019 to over 400 beds in 2021.

In essence, the number of homeless individuals did not necessarily drop—rather, more of them were indoors and less visible, thanks to active outreach and improved shelter access.

56%

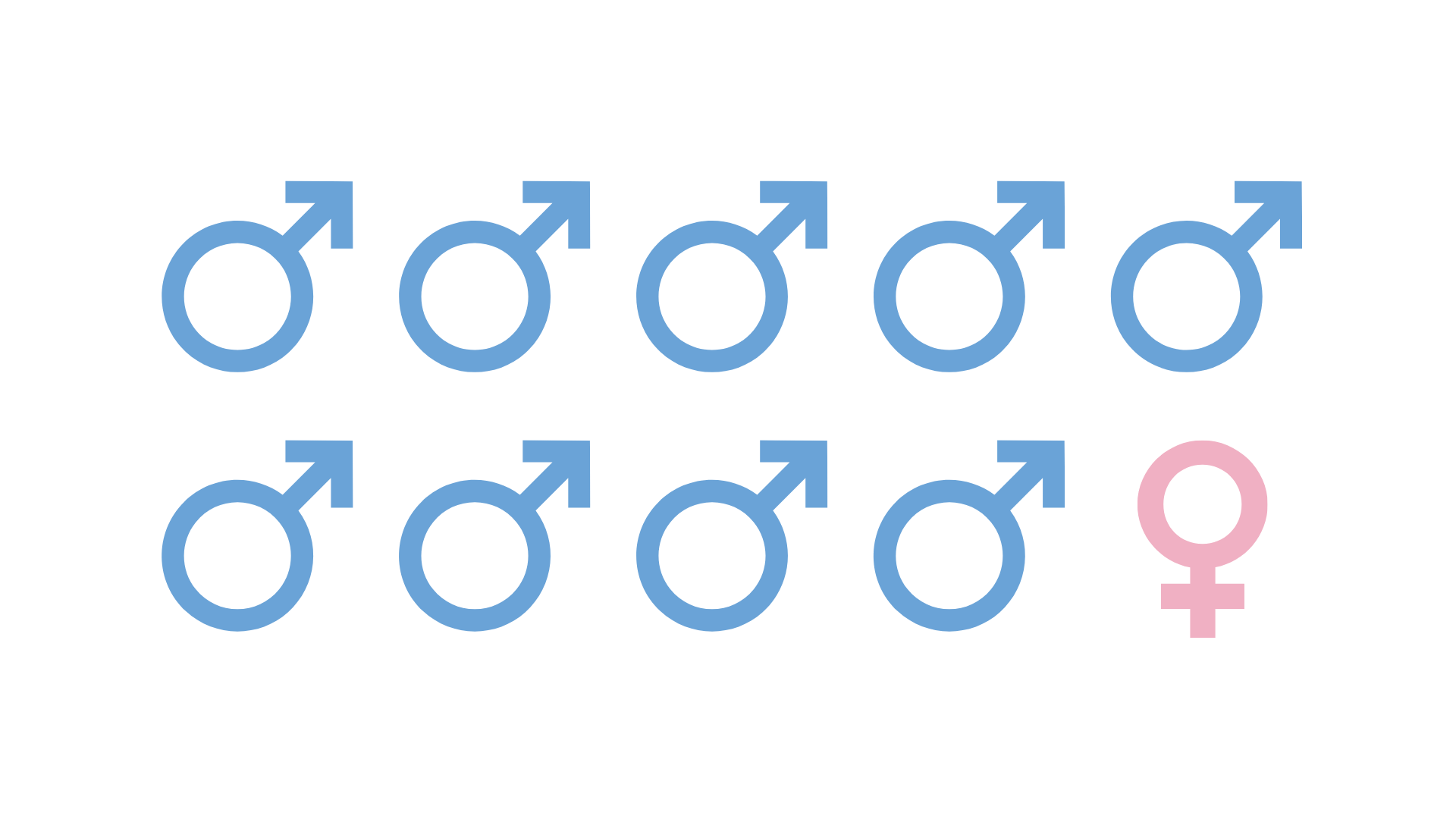

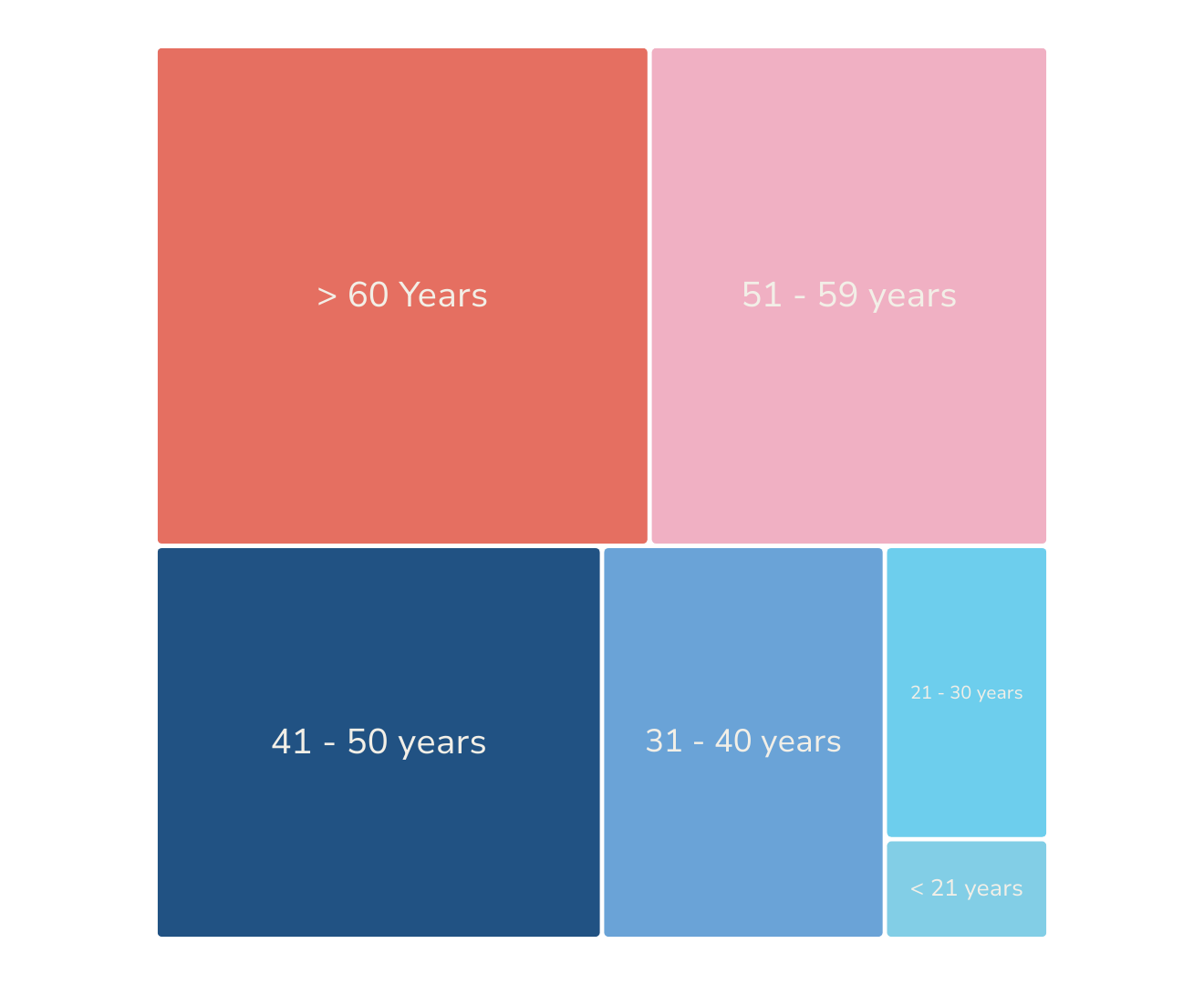

Homelessness in Singapore disproportionately affects older adults, especially single elderly men.

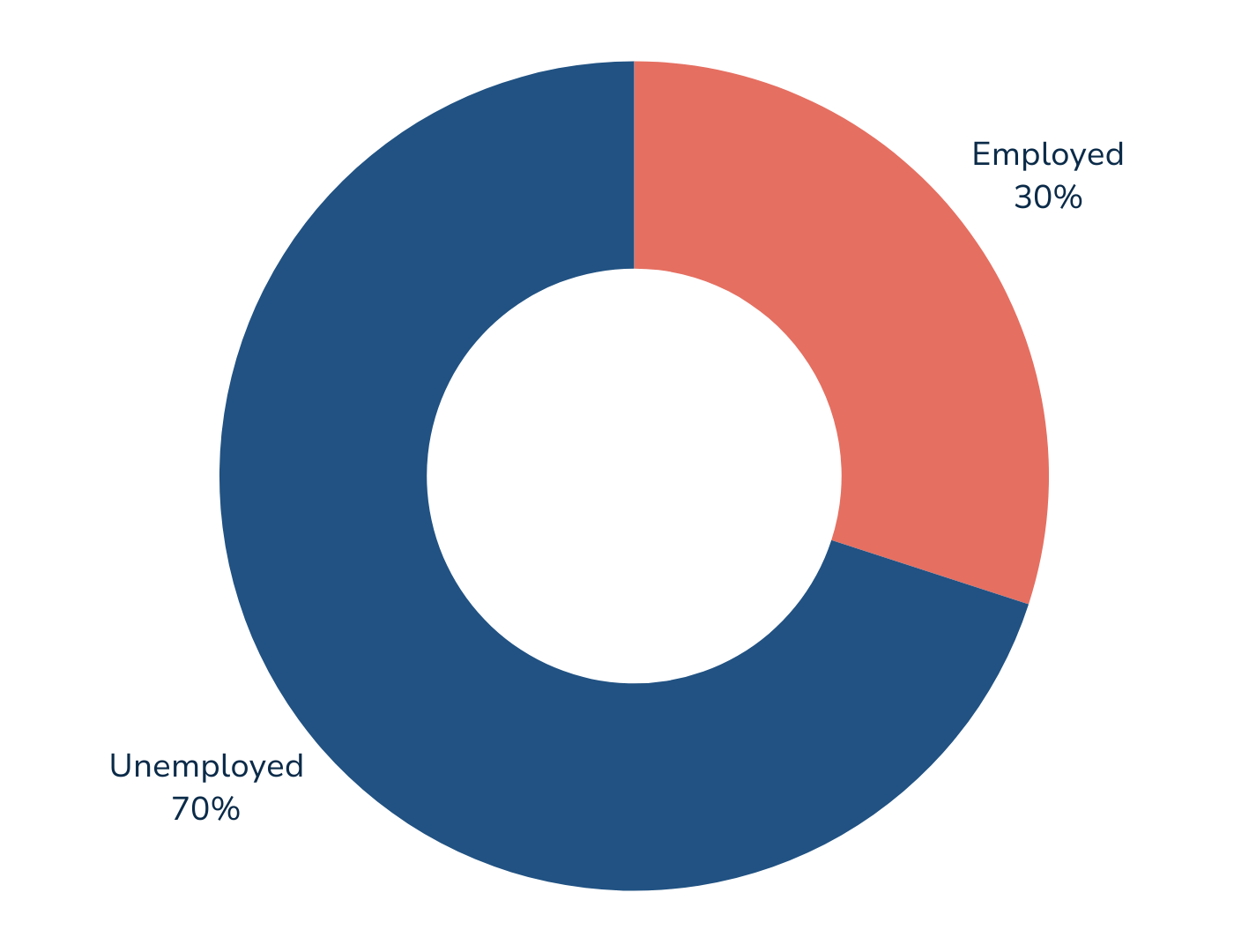

Younger homeless individuals tend to find short-term or hidden accommodations (secondary homelessness), making them less visible in street counts.Even among the unemployed, most had worked previously but lost jobs due to illness, caregiving duties, retrenchment, or age discrimination.

70%

30%

|

Housing History

Family Conflicts

Estrangement, divorce, or abuse leading to being forced outIneligibility for Rental Housing

Some do not meet criteria for HDB public rental (e.g., citizenship, family nucleus)Affordability Issue

Inability to pay rent due to low income or rising living costsEviction from Shared Rental

Especially in overcrowded flats or room rental arrangementsHealth Issues

Long-term illness leading to job loss and inability to afford housingLoss of Caregiver Role

After caring for an elderly parent or relative, they are evicted from the flat once the person passesTrailer - Setting Off

Episode 1 - This Is Why We Serve

Episode 2 - Every Journey Has A Beginning

Episode 3 - Champions For Change

Episode 4 - Let's Go On A Retreat

Episode 5 - One Foot In The Door